Read the other posts in this series:

Why Create an AX Build Server/Process?

Part 1 - Intro

Part 2 - Build

Part 3 - Flowback

Part 4 - Promotion

Part 5 - Putting it all together

Part 6 - Optimizations

Part 7 - Upgrades

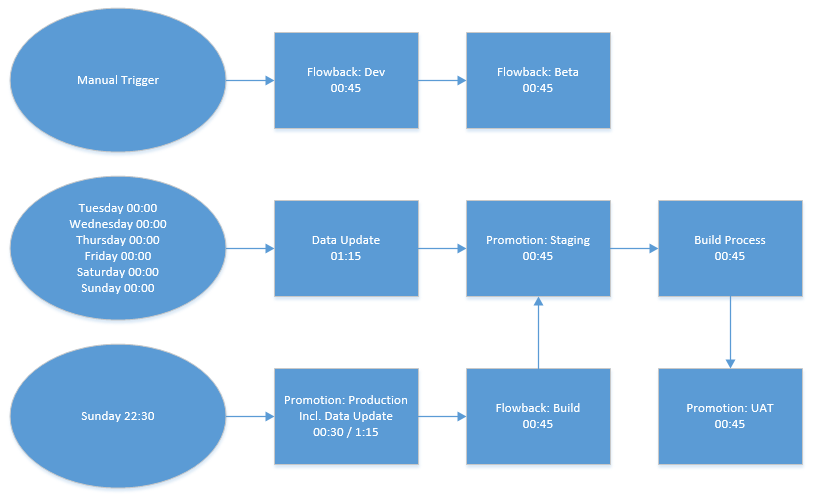

Up until now I have only been discussing what it has taken to get a Lifecycle Management system in place for AX 2009. The system needs to be reliable and adaptable while providing a comprehensive set of automated tasks to allow changes to AX to be propagated correctly. And like most programming projects, it was approached as a “Let’s get this in place so we have something as soon as we can”. However, inefficiencies can and do add up, so now it’s time to refactor our solution and make it more efficient.

For starters, we have replaced all of the scripts we use with PowerShell scripts for consistency. Since PowerShell is based on the .NET framework, we have the power and versatility of .NET. In some cases we are already using that power, but now we should really convert everything so there is consistency across the board.

In addition, we also noticed that many of scripts are redundant, with only minor changes from copy to copy. If something needs to change in the operations of one type of script, it would need to be changed in multiple places, increasing the chance of errors or inconsistencies. To fix that, we’ve generified majority of the scripts to so they are executed with parameters, which are defined by the specific build configurations. By extracting the differences to the TeamCity build configuration, we are able to turn each type of process (Promotion vs Flowback) into templates, allowing us to spin up a new process and only need to define the unique parameters for that process.

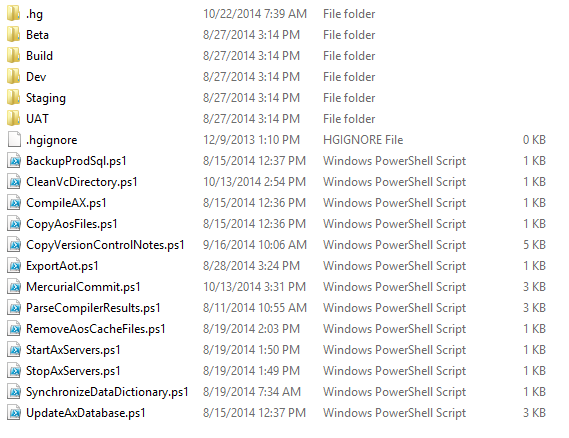

Instead of keeping the files segregated in their own process-specific folder, we’ve moved all of the generic scripts to the root of the version control repository:

We still have process-specific scripts, but those now only hold scripts that cannot be made generic, such as the SQL update scripts, which can’t be made generic as easily as the process scripts.

Here is an example of a script we have converted from a command line to PowerShell:

1 | [CmdletBinding()] |

In this case, we are passing in a folder location (in our case, the network share for the specific environment), iterating over a list of extensions and removing all files with those extensions from that location. In addition to being able to run for any of our environments, it also allows us to easily remove additional file types by simply adding another entry to the list. If we wanted to remove a different list of extensions for each environments (or the ability to add additional extensions to the default on a per-environment bases), we could extract that to be a parameter as well. However, since our goal is to have each environment be as close to production as possible, we opted not to do that.

Here is another example where we can take advantage of advanced processing to allow the script to run for multiple types of environments:

1 | #Note: default values may not work, as empty strings may be passed. |

This script accepts two parameters, the server name (which is mandatory) and the process name (which is optional). Additionally, it can accept multiple servers as a CSV string - we use this for our production environment, which is load balanced across three servers. The servers are started in the same order as they are passed in, and you only need to define the process name if it is different than the default “Dynamics AX Object Server 5.0$*” (for example, if you have two environments on the same server, so you only shut down one of those environments). We’ve also been able to include debug messages to verify what actions are occurring when changing the scripts, and confirm if you want the action to execute. These messages do not appear when executed by TeamCity.

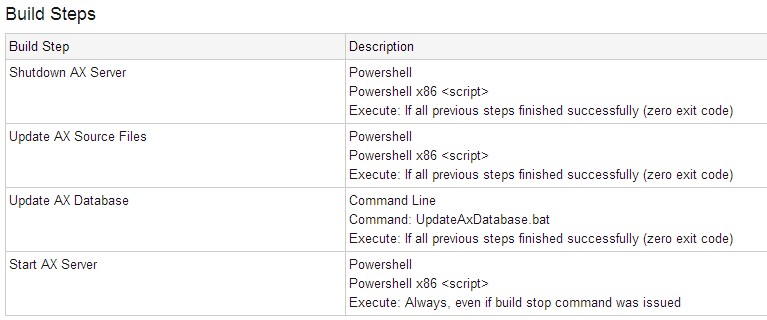

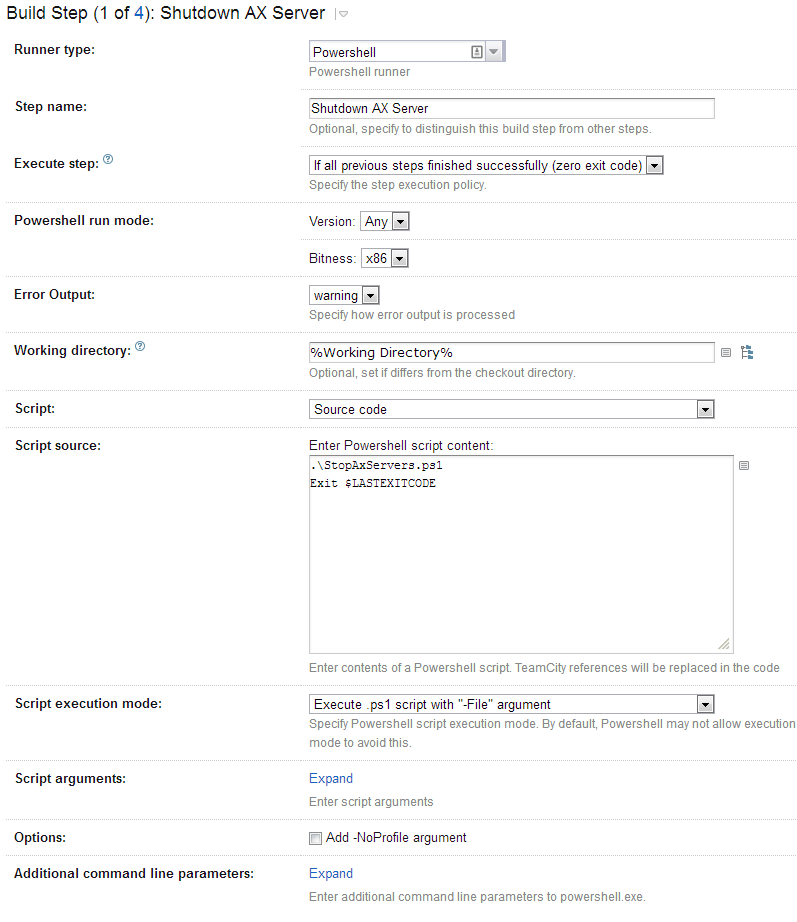

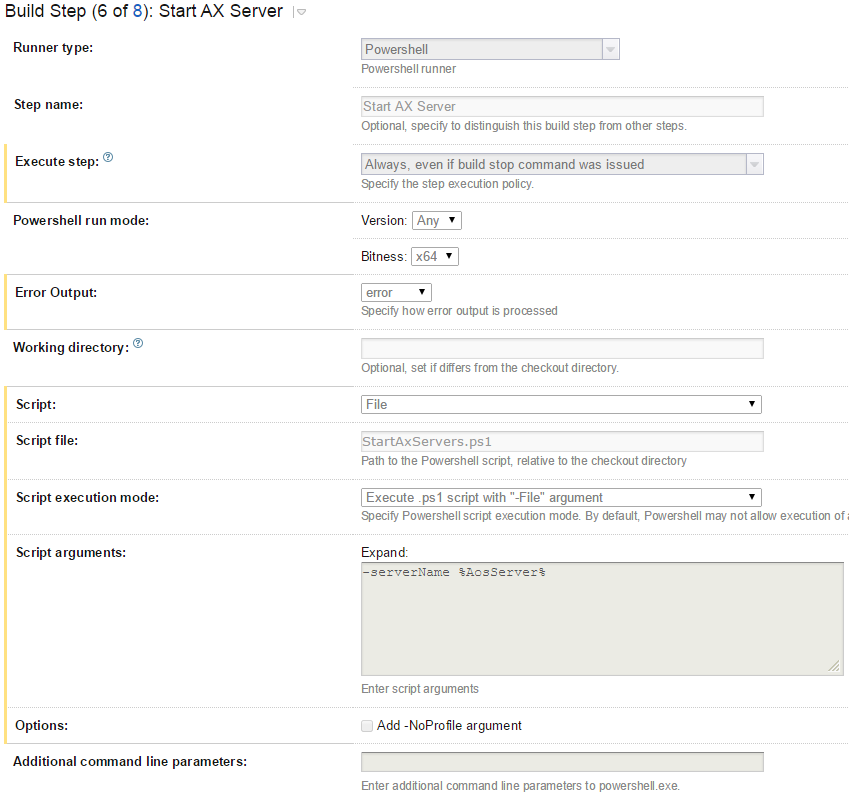

On the TeamCity side, this script would be configured as follows:

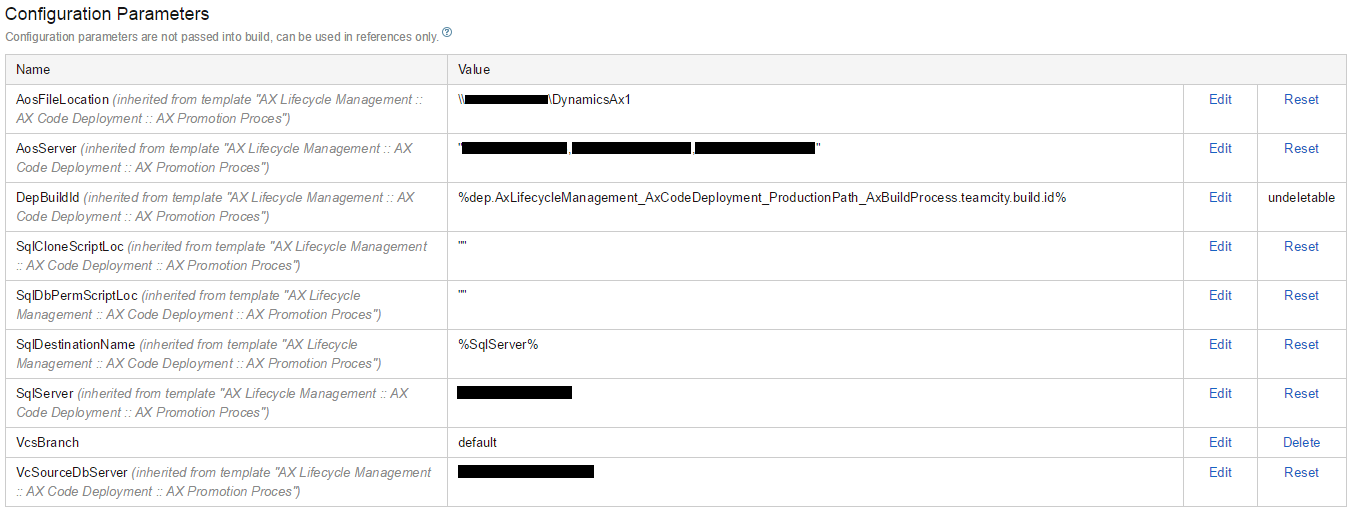

The %AosServer% in the script arguments section is a reference to a the configuration parameters of the build configuration:

Ultimately, these parameters drive the behavior of the entire process (which is why some parameters, like SqlServer, reference other parameters - because for this environment they are the same).

Finally, now that all the scripts are effectively applicable to all environments, it makes templating each of main processes easy, since all the scripts will take parameters. The parameters don’t need to have a value within the template, they only need to be defined - the configurations provide the actual values. You can see from the screenshot above that majority of the parameters are inherited from a template. We have the option to reset any of them to the default values (in this case, blank, as defined on the template), but we cannot delete them.

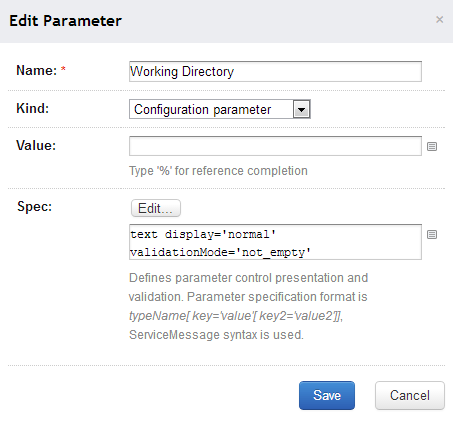

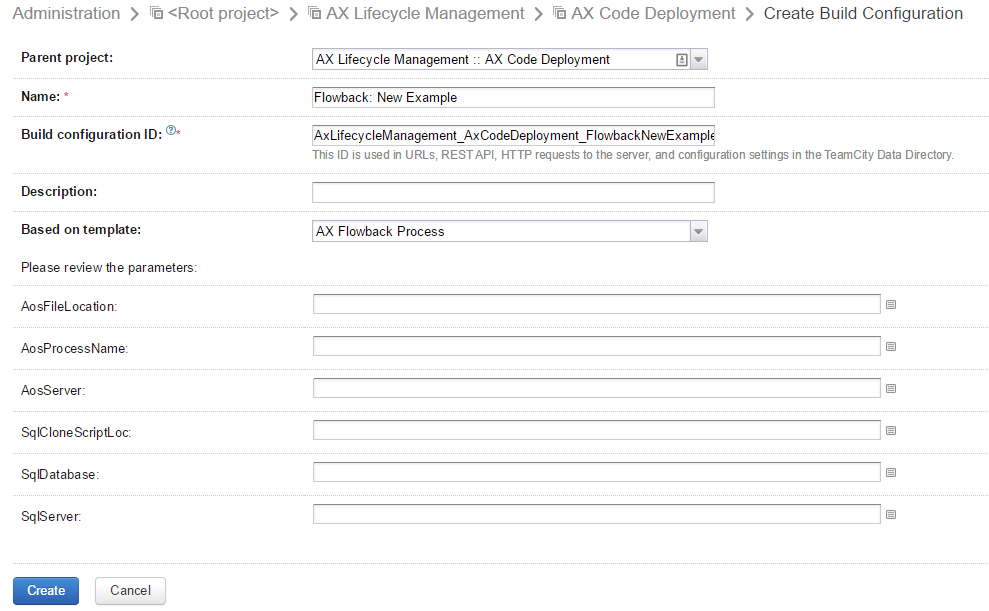

Each of the configuration parameters is also configurable within TeamCity so a value must be provided. If no value is provided, the configuration will not execute. The nice side of configuring a template this way is spinning up a new process is as easy as clicking a button and filling in some values:

From there, the only things you need to define are the triggers and dependencies, if you need more than those that are defined via the template.

Similar to the build scripts themselves, if there is a new process that needs to be added for each type of configuration (for example, a new step), we need only add it to the template, and it will automatically be added to all the configurations that inherit from that template.

The goal of all this is to decrease the amount of maintenance that needs to be done when a change needs to be made. By standardizing the language of all the scripts, less overall knowledge is needed to manage them; if a script generates an error, we need only fix one version of the script instead of 5; if a process is missing a step, we need only change the template configuration instead of 3-4 build configurations.

Here are samples for the scripts we have (not including the SQL files). Note that you may not need all these files:

1 | #Note: default values may not work, as empty strings may be passed. |

1 | [CmdletBinding()] |

1 | #Note: default values may not work, as empty strings may be passed. |

1 | $rootSourceLocation = "\\[Network location]" |

1 | [CmdletBinding()] |

1 | ax32.exe -startupcmd=compileall_- | Out-Null |

1 | #Note: default values may not work, as empty strings may be passed. |

1 | #Note: default values may not work, as empty strings may be passed. |

1 | #Note: default values may not work, as empty strings may be passed. |

1 | trap |

1 | [CmdletBinding()] |

1 | #Note: default values may not work, as empty strings may be passed. |

1 | #Note: default values may not work, as empty strings may be passed. |

Working on AX Lifecycle Management has shown a lot as far as how the AX infrastructure has been set up. While I’m sure this system may only have limited use in AX 2012 or AX 7 (if any at all), having a formal process has allowed me as a developer to focus more of my time on actual development without having to worry about how it is going to be deployed into our production environments. Having an automated environment update process allows me to track how changes impact the environment more realistically, so code changes are less likely to have problems when they do finally reach production. The built-in audit trail is fantastic for showing to auditors, both internal and external, what happened and when. And while we haven’t had the need to roll back an update it’s nice to know the possibility still exists if it is needed.

Ultimately, the system we have built is a very simple one - easy to understand, easy to explain, easy to show what exactly is going on. But the impact it is making has been huge - mostly because of its simplicity. I hope this series inspires others to implement similar systems for their organizations.